May 13, 2022

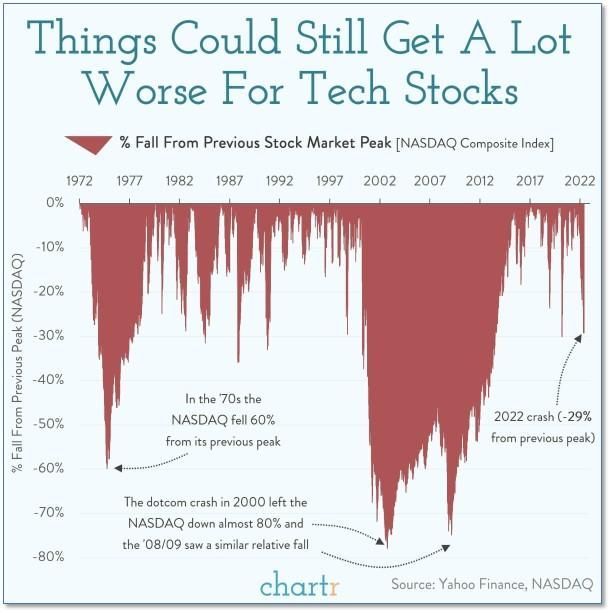

Usually it’s a newsworthy event when the price of a well-known tech company falls by more than 10% in a week’s time. However, in the last few weeks almost every single day has seen multiple major technology bellwethers taking double-digit losses. So, how bad can this get?

Cory McPherson is a financial planner and advisor, and President and CEO for ProActive Capital Management, Inc. He is a graduate of Kansas State University with a Bachelor of Science in Business Finance. Cory received his Retirement Income Certified Professional (RICP®) designation from The American College of Financial Services in 2017.

DISCLOSURE

ProActive Capital Management, Inc. (PCM”) is registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission. Such registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training.

The information or position herein may change from time to time without notice, and PCM has no obligation to update this material. The information herein has been provided for illustrative and informational purposes only and is not intended to serve as investment advice or as a recommendation for the purchase or sale of any security. The information herein is not specific to any individual's personal circumstances.

PCM does not provide tax or legal advice. To the extent that any material herein concerns tax or legal matters, such information is not intended to be solely relied upon nor used for the purpose of making tax and/or legal decisions without first seeking independent advice from a tax and/or legal professional.

All investments involve risk, including loss of principal invested. Past performance does not guarantee future performance. This commentary is prepared only for clients whose accounts are managed by our tactical management team at PCM. No strategy can guarantee a profit.

All investment strategies involve risk, including the risk of principal loss.

This commentary is designed to enhance our lines of communication and to provide you with timely, interesting, and thought-provoking information. You are invited and encouraged to respond with any questions or concerns you may have about your investments or just to keep us informed if your goals and objectives change.